Thank God I'm Not Like That Pharisee!

|

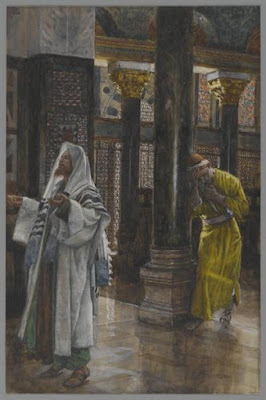

| "The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican" by James I. Tissot |

Click here to listen to this sermon.

“[Jesus] also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt” (Luke 18:9).

“[Jesus] also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt” (Luke 18:9).

Grace to

you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ!

“The

Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector” is one of the simplest of Jesus’

parables. Two men go to the temple to pray. One brings before the Lord his own

good works. The other has nothing to bring but a cry for mercy. Only one goes

home justified.

But this parable

is perhaps so familiar that its edge is dull and it has lost the shock of God’s

grace and the surprise of the Gospel. Our minds think of the characters

differently than those to whom Jesus first spoke it. So, I’d like to change it

just a little to see if we can’t recover some of its original bite.

Instead

of having the two guys go to the temple, let’s have them come to your house to pick

up your daughter for a date. Having three beautiful daughters, who were at one

time teenagers, this is a scenario quite familiar to me. But since some of them

are sitting in the pews, let me add a disclaimer: This illustration is

fictional. Any resemblance to actual events or persons is entirely

coincidental.

The first

guy who knocks at your door is well-dressed. He has a good and stable job,

plenty of money, and is well-respected in the community. But even more, he’s

that guy you’ve been hoping would come around. He goes to church every week,

reads his Bible daily, prays, fasts, and lives by the rules. His answer to the

“tell me a little bit about yourself” question is all the things you want to

hear. He’s not like the other guys, thank God. He’s a gentleman. You’re not

going to have to worry at all about your daughter being in this man’s care. And

as your daughter walks out the door, you tell her, “Be nice to this guy,” and

as soon as the door shuts, you start calling around to price caterers for the

wedding.

The next

night the second guy comes knocking. You know this guy. He’s been in a lot of

trouble. Runs with the wrong crowd. He’s the guy you’ve been warning your

daughter about all of her life. If you had known this guy was coming, you would

have made sure you were cleaning your shotgun when he came in through the door.

There’s no way you’d let your daughter go out with someone like him. Still,

he’s got gumption. He doesn’t leave right away, but starts admitting all the

things that he’s done wrong, and he tells you that he is trying to turn a new

leaf. As if one little apology could make up for a lifetime of bad decisions!

These are

the two guys Jesus is talking about. One looks holy, righteous, good. He comes

from a good family, is well-respected in the community, very active in the

church. The other is a low-life hoodlum.

And if

they were to both die on the way home that night, the golden boy would enter

the endless torment of hell and the ne’er-do-well would be carried by the

angels to the face of Jesus. Something about that doesn’t seem right, does it?

Kenneth

Bailey writes:

The more familiar a parable, the more it cries out

to be rescued from the barnacles that have attached themselves to it over the

centuries. In the popular mind, the parable of the Pharisee and the tax

collector is a simple story about prayer. One prays an arrogant prayer and is

blamed for his attitudes. The other prays humbly and is praised for so doing.

Too often the unconscious response becomes, “Thank God, [I’m] not like that

Pharisee!” But such a reaction demonstrates we are indeed like him![i]

So how

can this parable best be understood? Is it strictly about styles of prayer? Is

it about the difference between a “bad guy” and a “good guy”? No doubt both of these

elements are at play here, but Luke tells us right up front that the main focus

is righteousness and those who believe they can reach such righteousness by

their own efforts. “[Jesus] told this parable to some who trusted in themselves

that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt” (18:9).

What does

it mean to be a righteous person? In the Greek world “righteous” was a general

term that applied to a person who was civilized and who observed custom and

legal norms. Generally speaking, these meanings have placed their stamp on the

popular understanding of a “righteous person” even today. But the New

Testament’s roots are in the Old Testament where righteousness is more

concerned with relationships than actions. The righteous person is not the one

who observes a particular code of ethics but rather a person graciously granted

a special relationship of acceptance in the presence of God.

Again and

again in His teaching, Jesus presents the theme of the “righteous,” who do not

sense their need for God’s grace, and the “sinners” who yearn for that same

grace. Sin for Jesus is not primarily a broken law, but a broken relationship.

The tax collector yearns to accept the gift of God’s justification, while the

Pharisee feels he has already earned it. But God does not grade on a curve or

give extra credit. His only accepted standard is perfect righteousness. And

ever since the Fall, there’s only been one such person: The God-man who tells

this parable.

Now, that

you’ve gotten a better sense of how shocking this scenario would have been to

its original audience, let’s return to Jesus’ parable.

“Two men

went up into the temple to pray.” In English, we commonly use the word pray to

refer to private devotion and the word worship to refer to what a

community does together. In Semitic speech, “to pray” is used for both. On

Sundays, the Christian in the Arab world says to his friend, “I’m going to

church to pray,” and the friend knows the speaker is on his way to public

worship.

In the

parable a place of worship is mentioned specifically, and the two men are on their

way to pray at the same time, so it is reasonable to assume it takes

place during a time of public worship. Since the Sabbath is not mentioned it is

likely that this takes place during the week. The only daily services in the

temple area were the atonement offerings that took place at dawn and again at 3:00

p.m.

Each

service began outside the sanctuary with the sacrifice for the sins of Israel

of a lamb whose blood was sprinkled on the altar. In the middle of the prayers

there would be the sound of silver trumpets, the clanging of cymbals, and the

reading of a psalm. The officiating priest would then enter the outer part of

the sanctuary where he would offer incense and trim the lamps. When he disappeared

into the building, the worshipers would offer their private prayers to God.

The

Pharisee stands by himself and prays. He stands by himself because he is a

Pharisee, a name which comes from the Hebrew word for “separated.” The

Pharisees stressed keeping God’s Law and their traditions, and put great

emphasis on observing such rituals as washing, tithing, and fasting. They also separated

themselves from non-Pharisees because they did not wish to become unclean.

Because

he stands by himself he may well be praying aloud. Such a voiced prayer would

provide a golden opportunity to offer some unsolicited ethical advice to the

“unrighteous” around him who might not have another opportunity to observe a

man of his impressive piety! Most of us in our spiritual journeys have, at some

time or other, listened to a sermon hidden in a prayer. Regrettably, some of

us, present company included, have “preached” that kind of prayer.

The

Pharisee’s prayer begins, “God, I thank You that I am not like other men…” But

is what follows really a prayer? It’s neither a confession of sin, thanksgiving,

or a petition for oneself or others. Rather than comparing himself to God’s

expectations, he compares himself to others, enumerating his own

accomplishments: “I fast twice a week; I give tithes of all that I get.”

The

Pharisees thought of the Law as a garden of flowers. To protect the garden and

the flowers, they opted to build a fence around the Law. That is, they felt obliged

to go beyond the requirements of the Law in order to assure that no part of it

was violated. Without a fence around the garden someone just might step

on one of the flowers.

The written

Law only required fasting on the annual Day of Atonement. The Pharisees,

however, chose to fast two days before and two days after each of the three

major feasts. But this overachiever announces to God that he puts a fence

around the fence! He fasts two days every week. The faithful in the

Old Testament were only commanded to tithe their grain, oil, and wine. But this

Pharisee makes no exceptions, claiming simply, “I give tithes of all

that I get.” Surely those listening would be impressed by such a high standard

of righteousness.

And the tax

collector? Sensing his defiled ceremonial status, the tax collector chooses to

stand apart from the other worshipers in order to pray. The accepted posture

for prayer in the temple was to look down and keep one’s arms crossed over the

chest, like a slave before his master. But the tax collector is so distraught

over his sins that he beats his chest where his heart is located. In the Middle

East, generally speaking, only women beat their chests; men do not.

Occasionally, women at particularly tragic funerals beat their chests.

In the

Bible, the only other case of people beating their chests is at the cross when

the crowds (presumably both men and women), deeply disturbed at what had taken

place, beat their chests just after Jesus died (Luke 23:48). If it requires a

scene as distressing as the crucifixion of Jesus to cause both men and women to

beat their chests, then clearly the tax collector of this parable is deeply

distraught!

And

notice what the tax collector says as he engages in this extraordinary act.

Most English translations render his prayer with the words: “God, be merciful

to me, a sinner.” But this text does not use the common Greek word for “mercy.”

Instead, it uses a theological term that means “to make atonement.” A more

literal rendering of his prayer would be, “O God, make atonement for me.”

Not only

that: Remember where this takes place—in front of the altar in the temple

courtyard. The tax collector listens to the blowing of the trumpets and the clash

of cymbals, hears the reading of the psalm, and watches blood splashed on the

sides of the altar. He sees the priest disappear inside the temple to offer

incense before God. Shortly afterward, the priest reappears announcing that the

sacrifice has been accepted and the sins of Israel’s people have been atoned.

The trumpets blow again, and the incense wafts to heaven. The great choir sings,

and the tax collector, beats his chest and cries out, “O God, make atonement

for me, a sinner!”

Jesus declares,

“I tell you, this man (the tax collector) went down to his house justified,

rather than the other.”

Whenever

I hear this parable, my initial reaction is “Thank God, I’m not like that Pharisee!”

But such a statement proves that I am just like him. You are, too! There’s a

Pharisee inside of each of us. Old Adam, is at the core, proud and self-righteous.

By nature, you’re tempted to believe that God loves you because of something

about you. If you’re attractive, you’re happy that you’re better looking than

others. If you’re smart, you’re happy that you’re smarter. If you’re a hard

worker, you’re happy that you’re not a slacker like so many are today.

That is

simply how the sinful nature makes you think: you measure yourself by how you’re

better than others. You find your worth in what you’ve got that others don’t.

It can be a subtle form of contempt, but it is contempt all the same. And if

that is how you think, then that is how you present yourself to God: “God, I’m

happy that I’m not like those other people.” And there you go, sounding just

like the Pharisee. But the truth is this: standing before God is a great

leveler. No matter the amount of giftedness, all have sinned and fall short of

the glory of God. Your worth, your value before God does not come from who you

are, but whose you are. Your worth before God does not come from

yourself, but from the truth that you have been bought by the blood of Christ,

crucified and raised for you.

And so

you can gratefully confess: “Thank God, I’m not like that Pharisee! Oh, I’ve

sinned like him, that is sure. I’ve looked down on others and held my

self-righteousness before God. But like the tax collector, I confess that I am

a poor, miserable sinner who has offended God with my sins and justly deserves His

temporal and eternal punishment. But I am heartily sorry for them and sincerely

repent of them, and I pray, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’ For the sake of

the holy, innocent, bitter suffering and death of Your beloved Son, Jesus

Christ, be gracious and merciful to me, a poor, sinful being.”

Upon this

your confession, God’s called and ordained servant announces God’s grace unto

you. In Baptism, you were clothed with Christ’s righteousness, adopted as a

child of God, and given the gift of the Holy Spirit. The bread and wine given to

you at this altar are Christ’s very body and blood, given and shed for you for

the forgiveness of your sins and the strengthening of your faith.

You go

home justified. Almighty God, our heavenly Father, has had mercy on you and has

given His only Son to die for you. You are forgiven for all of your sins.

In the

name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen

Unless

otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, English

Standard Version, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of

Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

[i] Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes: Cultural Studies in the Gospels,

343 (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008).

Comments